Discovering Tokaj’s Sweet Secrets: At Home in Erdőbénye

9 minutes read

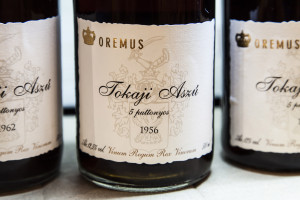

Winemakers in Tokaj, the famed wine region in northeastern Hungary, are singularly obsessed with a fungus. No ordinary fungus, it is botrytis (or “noble rot”) which they are mad about. It is the ingredient which magically transforms their precious ripe grapes into the shriveled, small, raisin-like berries which make Tokaji aszú one of the world’s greatest sweet wines. The wine is the pride of Hungary, yet unfathomably, it is still practically a secret among the majority of the world’s wine drinkers. Winemakers in Tokaj rely on botrytis, which only occurs when weather conditions are perfect, to concentrate sugars and flavors in the shrivelly grapes. This results in rich, golden-colored wine that can taste of orange marmalade, hazelnut, bread, dill, citrus, apricot, honey, or a host of other flavors. These dried grapes are the backbone of Tokaji aszú and are not only hand-harvested, but are selected one by one.

It’s an exceedingly special wine, with a long-lingering finish and the potential to age for decades, even centuries.

Tokaji aszú is a complex, traditional wine, which has been admired by royalty and popes, and is even praised in the Hungarian national anthem. As an expat who has been living in Budapest—200 kilometers from Tokaj in the southern foothills of the Carpathian Mountains—for around a dozen years, I slowly, but seriously, became so smitten with it that my husband, Gábor, and I fantasized about having a little piece of this dreamy place for ourselves.

I had become fascinated by these winemakers (though I secretly wondered if they were crazy) who go to such lengths and expense to make a traditional wine which defies so many current wine trends. “Over time producers here began to recognize that the botrytis berries should be separated and that a wine should be made with only those berries,” said Ronn Wiegand, a master of wine and master sommelier, speaking at the Digital Wine Bloggers Conference in October 2014. Ronn moved from California to Tokaj a few years ago and he now helps his wife and her family make wine at Erzsébet Pince, a lovely family winery in the center of Tokaj. “Tokaj is the world’s first botrytis culture, where the focus on making wine from these botrytized berries is on an industry-wide basis,” said Wiegand. The botrytized wines from Tokaj are so powerful that once you inhale their aroma of blossoms, orange, honey, and spices, the scent will become a lasting memory.

On a cold October evening a few years ago, while Gábor and I sat in a Budapest lawyer’s office, raisin-like grapes were still being harvested in Tokaj (in extraordinary years the harvest can even last until December). We were meeting with five elderly siblings who were selling us the house in Erdőbénye—a village in the center of the region, surrounded by the wooded Zemplén hills—which grew up in. As they reminisced about all the plum pálinka they had distilled from the dozens of fruit trees in the wild yard, one of them suddenly asked: “Do you want our vineyard too? It’s not a famous one, only about a half-acre, but our dad planted it and made wine from it. We have no use for it now.” Gábor and I looked at each other wide-eyed. “Yes,” he blurted, as we both thought the same things: this adventure was taking on another dimension, and, what on earth will we do with a vineyard?

Just as a glass of Tokaji aszú has layers of subtle flavors which slowly reveal themselves, our adventure of being part-time locals has been about discovering the layers in the region. The area is a UNESCO World Heritage site consisting of 27 villages between the Zemplén hills and the Bodrog river, close to the borders with Slovakia, Romania, and Ukraine. Wine has been made here since at least the 13th century and Tokaj’s vineyards were the world’s first to be delimited in 1737. The area is defined by hundreds of gently sloping hills patched with carefully tended rows of vines. These hills were volcanoes which erupted millions of years ago and left a variety of rocks in shades of red, orange, white, and yellow. This geological history has created hundreds of different terroirs, which make some pretty interesting wines (as well as great rock-collecting walks). There are a few large state-of-the-art wineries (such as Disznókő, Dereszla, and Oremus). But mostly, wineries here are smaller family affairs operating on a few acres of vineyards, sometimes without even a sign.

The best of these wineries make true terroir wines from this ancient and varied soil.

Erdőbénye has an impressive wine pedigree. The Rákóczi family, Transylvanian royalty who came to this region in the late-16th century and subsequently acquired most of it, were the “premier family in the history of modern [Tokaj] botrytis wine,” according to Tokaji Wine: Fame, Fate, Tradition by Miles Lambert-Gócs. Erdőbénye became theirs in 1616 when Prince George Rákóczi I. married Susanna Lórántffy. They built a vast multi-level labyrinth of a wine cellar under the village. Today it mostly sits, unused, though a portion can be visited at the Illés Winery, a family winery which solely sells its wines at the cellar door. It was Susanna’s vineyard manager, László Szepsi, who is credited with making the first modern aszú from botrytized grapes. According to the story, Szepsi postponed the harvest because the Ottomans were invading. By the time it was possible to harvest, the vines were full of botrytized grapes which he used to make aszú. However, accounts vary, and history does not agree on exactly what his role in the development of aszú was.

“Undeniably, there is an aura about Szepsi: he ranks among the very few persons to whom a kind of wine is attributed. He could be called the Dom Perignon of Hungary,” writes Lambert-Gócs. “From all the fanfare about him in Hungarian history, it can be hardly doubted that he made a major contribution of some sort, a contribution that profoundly affected the fabrication of botrytis wines in [Tokaj].” Szepsi spent much time in Erdőbénye, and a László Szepsi Memorial House on the main street honors him.

Erdőbénye’s main street is lined with elegant houses from the 19th and early 20th centuries, some of which were once owned by Armenian or Jewish wine merchants (before the Holocaust nearly a quarter of the region’s population was Jewish). Most houses have long, narrow mould-covered wine cellars, and several house small wineries. Most are small ventures which have started in the last 10-15 years. Winemakers like Zsolt Berger at Karadi-Berger, Krisztian Ungváry at Vayi, Adám Molnár at Bardon Winery, and Atilla Homonna are making fine dry furmints and hárslevelűs, as well as some sweet wines. One of the newest arrivals, Budaházy Fekete Kúria Winery, is located in a commanding castle-like house at the beginning of the main street, and has also started making wonderful dry furmint and hárslevelű. Berger makes an unforgettable dry szamorodni, a traditional style of Tokaj made from a mix of ripe, overripe, and botrytized grapes. It is nutty and spicy, can be fermented sweet or dry, and is reminiscent of sherry.

The best time to taste these wines is at the annual three-day wine festival called Bor, Mamor, Bénye (Wine, Shine, Erdőbénye), which has gained the village many fans. All of the village’s wineries open, offering good food and hosting bands. It brings thousands of people who wander from winery to winery to eat, drink, and enjoy expansive views of the Zemplén hills.

The countryside life is bliss for our city kids, who love spending entire days outdoors, climbing trees, snacking on freshly-picked-fruit, and making friends with the local animals. A winding stream runs in front of the house, and the only sounds at night are chirping crickets and the trickling stream. A crumbling staircase in the yard leads up a steep hill to a secluded, overgrown, half-acre of yard with fabulous 360 degree view of church steeples on one side and gently rolling hills on the others. The house has a 75-foot long hand-carved cellar dug into the rhyolite tuff behind the house. We weren’t exactly sure what we were looking for when we followed this crazy idea of buying a house in Tokaj, other than an adventure. But we are happy to experience so much more of the region, beyond the wine.

Though Erdőbénye is not as prominent as some of the region’s other winemaking centers (such as like Mád and Tokaj), it’s an important center for the cooperage industry. Oak from the Zemplén hills is used to make high-quality barrels which are exported around the world. Cooperage is an old trade around here, and there are several coopers in the village who still make barrels by hand the traditional way (just watching the labor-intensive process makes my hands hurt).

It was sweet Tokaji aszú—the region’s most prized product and biggest claim to fame—which sparked our passion for this region. But not everyone here is has a passion for botrytis. Our neighbors do not drink aszú. The reality is that this is Hungary’s poorest region, which produces the country’s most iconic luxury product. Like elsewhere in Hungary, the drink of choice is often pálinka—homemade, and poured from a re-purposed soda bottle. In August the plum trees scattered around the village are heavy with plump plums. They are collected in big plastic vats to ferment, and then are taken to a community distillery to turn into pálinka. When we arrive in Erdőbénye after a long drive from Budapest, we are as happy to be greeted by our neighbor with a glass of his homemade plum pálinka as we would be if it were the finest aszú. The drinks are totally antithetical to each other: the pálinka is rough and warms you to your bones and the aszú is refined with subtleties that you could consider over a lifetime. But now, both taste like home.

Want to taste a bunch of different Tokaji wines? Visit The Tasting Table Budapest (and don’t forget to check out our selection of old and rare Tokaji aszú). Order from our menu, or book one of our daily tastings: Wine, Cheese, & Charcuterie Tasting and Essentials of Hungarian Wine Tasting).

Comments(0)

Leave a comment!