The Lost World of The Jewish Wine Trade in Hungary (and The Old Habsburg Empire) Part I.

7 minutes read

There’s no denying that the Hungarian wine industry has come a long way since Communism ended in 1989. The story of the first generation of winemakers—as well as the foreign investors who brought know-how and money—to re-start the wine industry in the early 1990s is a compelling one which has been often told. But what about the Hungarian wine industry before 1990? The unfortunate Communist period, during which quality was not a concern and winemakers were expected to hand over their wines to the cooperative to be unceremoniously mixed together, is part of the narrative. And the story of phylloxera wiping out much of the vineyards during the late 19th century is also an important part of the story, which is often told.

But what about the rest of the story, particularly the period when Hungarian wine was renowned around the world? There was a time when Poland was the major export market for Hungarian wine (and the Poles are still crazy about Tokaj aszú) and Tokaj sweet wine was sold all over the world, praised by royalty, politicians, and popes. When I visited Monticello, the home of Thomas Jefferson, Virginia, I was happy to see that a plaque stating the countries where his sizable wine collection came from included Hungary. This story of how the Hungarian (and Central European) wine trade functioned before the two world wars and communism is not a well-known one, and the practicalities of how the bottles got from their sleepy countryside villages of origin to the tables of fine restaurants around the world is a forgotten part of the story.

Europe’s terrible 20th century did its best to demolish the intricate old trade channels. Hand-in-hand the Nazis and the Communists ensured that few traces remained, and that the entrepreneurs who built businesses that spanned generations and connected Central Europe with the rest of the world, were largely forgotten. Of course, many of these businesses were Jewish ones. Even though some were really big and influential operations, it is not easy to find information on them.

I have been researching Central European wine history—particularly how Jews were involved for centuries in the wine trade and in winemaking—over the past few years. I found this untold story: a fascinating back story preceding the takeover of the state-owned coops, which lasted more than forty years (and devastated Hungarian wine). The family names and trading houses that I have been reading about were big players in the European wine trade in their day, only to have their stories forgotten. Here are a few brief stories of some of the families …

Ber Birkenthal

Let’s start at the beginning. The oldest document I came across was the memoir of Ber Birkenthal, a merchant who successfully navigated the entire Central European region, focusing his life on buying and selling Tokaj wine. He was born in 1723 in the town of Bolechow in Eastern Galicia (today’s Ukraine), and had a long and interesting life (he died in 1805). His memoirs, originally written in Yiddish in the 1790s, are an important source for learning about the wine trade and the society of the period. It’s clear that the Tokaj wine he was selling was not just a simple commodity for him: he had a real passion for it.

He started in the wine trade at the age of 20 and made dozens of trips from Bolechow to Tokaj. Today this trip, which is about 350 kilometers, would likely take a whole day of driving. But his trips were made on horseback. And on the return journey, between 50 and 70 barrels (but sometimes up to 200) were transported on horse-carriages. It must have been a strenuous journey—especially considering how bad the roads are even today—involving much planning, risk, and attention to logistics.

Ber Birkenthal was from a Jewish family that had been involved in the Tokaj wine trade for at least a generation and had established good relationships with Hungarian winemakers. His father, Judah, ran an inn and was the one who founded the wine business, which he later handed over to his sons. Judah was multilingual, having equally mastered Polish and Hungarian, and speaking Yiddish as a native language. He once even served as a translator for Ferenc Rákóczi II. As a well-traveled man, he had his son, Ber, educated in languages that he thought were important (and a Christian tutor taught his son Polish).

This family is a real example of how Jewish merchants tried to serve as intermediaries between different nations and social classes. He sold wine to Armenian and Greek traders, as well as Russian and Polish aristocrats. Language was probably only one of the many skills required for this. Courage must have been another, as Ber lived in a turbulent era, full of changes and wars. Traveling the roads between Galicia and Tokaj was a dangerous venture, and these guys were like Jewish cowboys carrying their guns as they crossed the Carpathians.

For most of his life, Ber Birkenthal lived in the Kingdom of Poland, but from the second part of his life (the 1770s) the Empire of Poland-Lithuania slowly disappeared from the map, and was divided between Austria, Prussia, and Russia. Krakow and Galicia (including Lemberg, Brod, and Bolechow) became part of the Habsburg Empire. Around this time massive numbers of Jews from Galicia started to settle in Hungary, including many in the Tokaj region. Many of them slowly but surely got involved in the wine business.

The Zimmerman Family

Apart from Ber Birkenthal, who actually never lived in Tokaj, we know of many Jewish families who settled in the Tokaj region and became successful traders of Tokaj wine. The village of Mád was a particularly important trading center where many Jews began settling from the mid 1700s. As time went by, and one generation followed another, these families were able to set up serious businesses. Most of them had become perfectly assimilated and did not take Jewish traditions very seriously. The family that might have been the most successful is the Zimmerman family. Their elegant house was in the very center of town, in the building which is now the headquarters of the Royal Tokaj Winery.

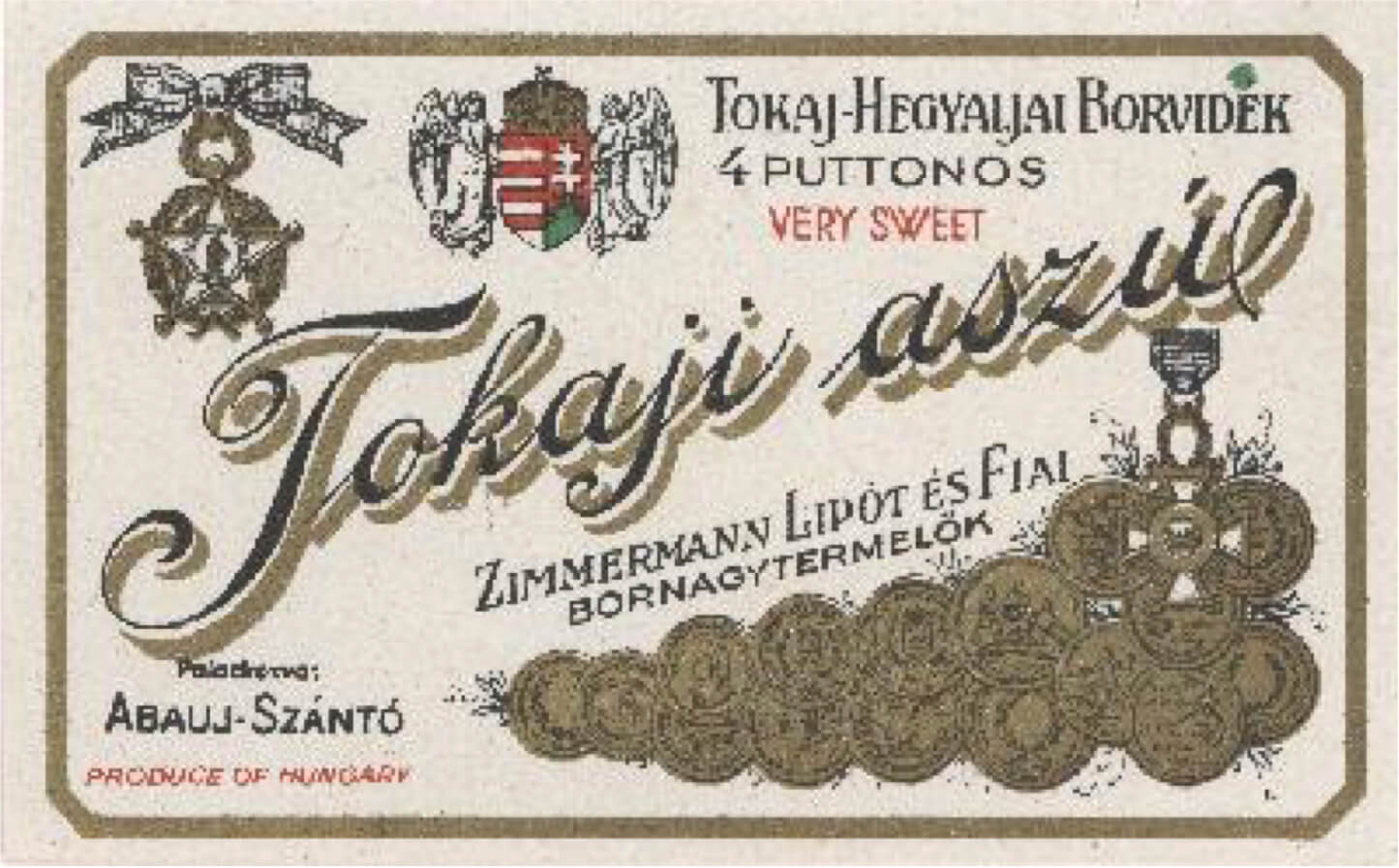

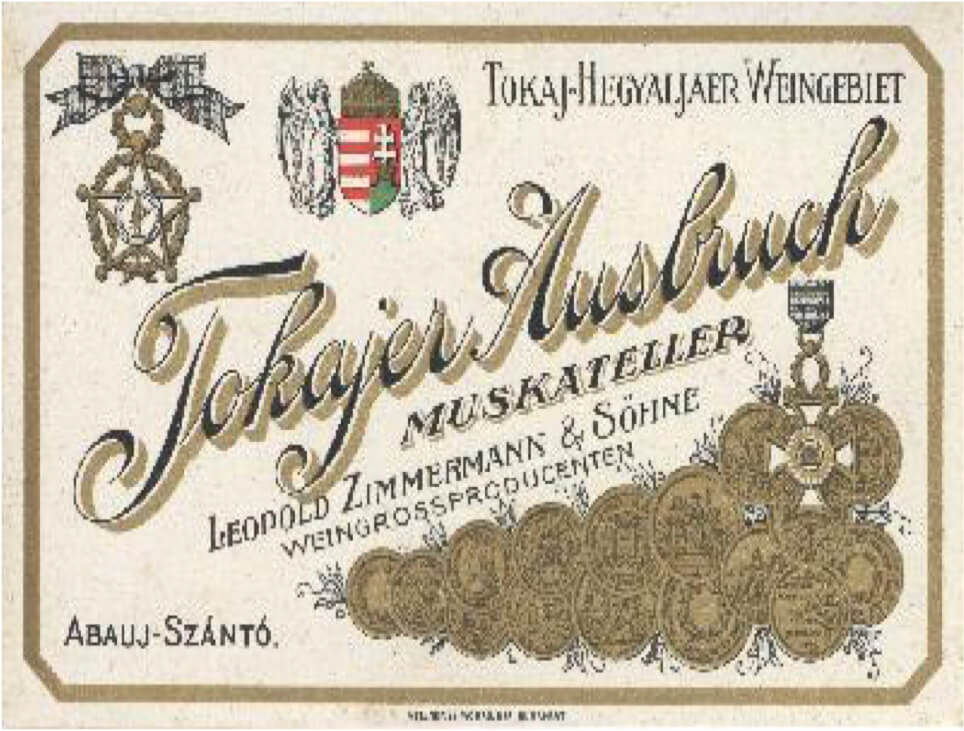

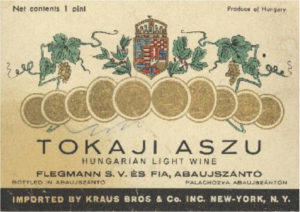

This spring I had the honor of visiting Mád with Beverly Fox, one of the descendants of the family Zimmerman. The family was a non-religious one, never going to synagogue. The Zimmerman family house in Mád is where her mother spent her childhood, and never returned after being deported to Auschwitz. During Beverly’s visit, we visited the old family home, the temple from the 1700s, and the cemetery outside of the village holding many fancy Zimmerman tombstones. The family had around 60 cellars scattered throughout the region, dozens of different vineyards, and houses not only in Mád, but also in Abaújszántó. Their wines won gold medals at competitions in Berlin in 1892 and Paris in 1896 and the company had sales offices in Budapest, Berlin, Katowice, London, and New York. Their labels can still be seen at auctions.

Learn more about the history of the Jewish wine merchants and community in Tokaj on our Tokaj Jewish Heritage & Wine Tour.

Comments(0)

Leave a comment!